When discussing Flow Virtual Networking, We already discussed Network Policies, simple stateless policies that can be enabled at the virtual router level to allow or deny traffic as it enters or leaves the VPC or passes between VPC subnets. Flow Network Security extends the security functionality to include full microsegmentation policies, leveraging OpenFlow to police traffic as it passes through the OVS bridges.

You’re probably already familiar with microsegmentation and its benefits on some level: traditional firewalls can only police from network to network and don’t provide any protection between machines on the same network. That’s where Flow Network Security comes in, providing an easy to use, fully distributed, line-rate, VM-to-VM firewall that works on any Nutanix AHV environment (on-premise AND NC2). To break that down a bit:

- Easy to Use – Our interface is designed to be easy to understand and use for everyone, breaking down barriers between security teams and application owners.

- Fully Distributed – FNS runs at the hypervisor level, allowing policy to be enforced efficiently and at scale.

- Line-Rate – FNS is efficient, providing security without slowing you down.

- VM-to-VM – FNS rules act on traffic at the VM vNIC level, allowing you control traffic between VMs even on the same network.

So why do we need Flow Network Security? What do we gain from a fully distributed, line rate, VM-to-VM firewall? Plainly speaking, properly configured microsegmentation is one of the best defenses against the spread of malware/ransomware. These exploits are built to quickly move laterally within a subnet, looking for ways to move to other networks. With Flow Network Security, you can ensure that only your essential business traffic is allowed, closing the holes that unwanted/unused services can create. So now that we know the what and why, let’s talk about the how.

As of September 2025 when this was updated, per the Nutanix Cloud Platform Software Options page on Nutanix.com, these microsegmentation capabilities were available either as an add-on to NCI-Pro or included in NCI-Ultimate.

Categories & Entity Groups

Policies are applied to VMs by way of Categories, either directly or by way of a category being referenced in an Entity Group1. You cannot directly assign a policy to a VM. If a policy needs to reference an individual VM, that VM can be placed in a category by itself.

Categories

Categories are key-value pairs used to define groups of VMs. A category is made up of an attribute and a value, such as AppTier:DB, AppTier:Web or Application:PublicWebsite. Attributes can have multiple values, as we see by having multiple AppTier categories. We can also group VMs by their environment using categories like Environment:Production and Environment:Dev. VMs can, and generally should, be in multiple categories as well. For example, if we have both a Production and Development instance of a public website, we can tag the web servers as shown.

There are many pre-defined categories, but you can also create them freely to match how a particular organization defines their workloads. Common attributes organizations might use include Environment, AppTier, Application, OperatingSystem, SecurityZone, or Department.

Categories are widely used throughout the Nutanix platform, such as to define Disaster Recovery Protection Policies and Recovery Plans.

It is possible to automatically assign VMs to categories by way of Playbooks. This is beyond the scope of this material, but the Nutanix developer resource site, Nutanix.dev, has a sample playbook that demonstrates auto-categorization by VM OS if you are interested in learning more.

Entity Groups

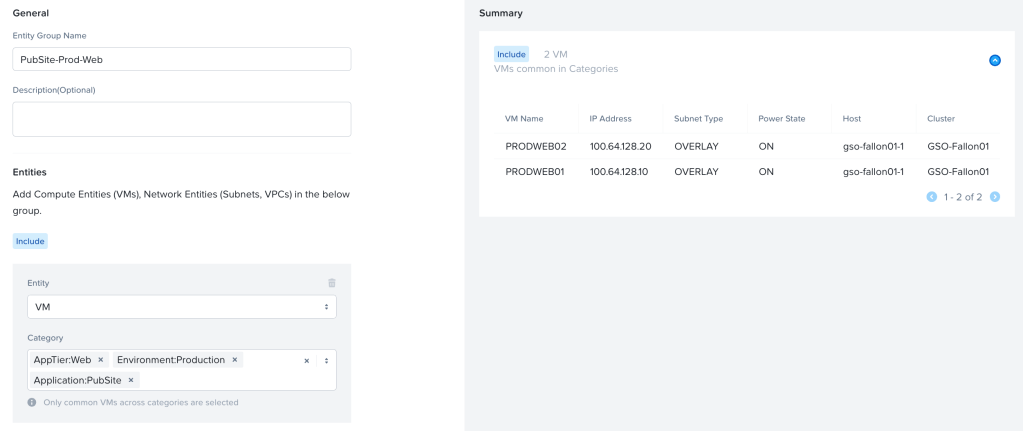

New in Flow Network Security 5.2, Entity Groups are a construct that allows you to build dynamic groups based on combinations of security tags. For example, an Entity Group PubSite-Prod-Web can include the VMs that have the three categories Application:PubSite, Environment:Production, and AppTier:Web. This entity group can then be used in a security policy.

Policy Types

There are four types of security policy, Quarantine, Shared Services, Isolation, and Application, which are evaluated and applied in that order. Within Application Policies, we also have VDI policies that use Active Directory group membership to secure VDI Desktops. FNS Policies are IPv4 only today. Within a policy, IPv6 traffic can either be completely blocked or completely allowed. If IPv6 is not blocked, all IPv6 traffic between defined sources and destinations are allowed. It is recommended that IPv6 be blocked unless specifically needed.

Policies are applied to a specific scope. Policies can be scoped to VLANs only, or to one or more VPCs, and as of FNS 5.2, they can also be applied to the Global scope to secure VMs across any VPC or controller-backed VLAN.

Quarantine & Isolation

Quarantine policies and Isolation policies are similar in that they are both intended to explicitly block unwanted traffic.

Quarantine

Quarantine policies are, as one might imagine, for quarantining VMs that are suspected or known to be compromised.

There are two built-in categories, Quarantine:Forensics and Quarantine:Strict, that are used for Quarantine policies. A Quarantine Forensics Policy and a Quarantine Strict Policy exist by default for VLAN subnets and are automatically created for each new VPC.

The Strict policies block all traffic to and from a VM completely in order to fully isolate a compromised VM. These policies cannot be modified, and an example can be seen below.

The Forensics policy is intended to allow VMs to be quarantined while still being reachable by specific tools for investigation. By default, the Forensics policies also block everything, but inbound and outbound rules can be configured.

VMs can be quarantined manually via Prism Central, or via automation triggered by an external source. For instance, an anti-virus or anti-malware tool that detects suspicious activity on a VM could send an API call to Prism Central to quarantine the VM.

Isolation

Isolation policies are, when enforced, explicit deny policies for ensuring that two or more environments do not communicate. For example, a Dev/Test/QA environment can be isolated from Production to ensure that a misconfiguration does not result in Dev/Test/QA workloads accidentally writing to a Production database. Isolation policies specify two or more categories and either monitor or block all traffic between the categories. One important caveat is that isolation policies can be bypassed by way of floating IPs, as they presently do not account for floating IP assignments when calculating destination traffic, so caution should be used when using floating IPs in conjunction with isolation policies, as additional steps will be required to prevent unwanted traffic.

Application & Shared Services

Application policies and Shared Services policies are both configured in a very similar manner. Application policies are the most common and the linchpin of an FNS implementation, so we’ll start with those.

Application Policies

In our Application-Centric Policy Model, we take the approach where, instead of a single monolithic list of firewall rules for your entire environment, we manage security policies on a per-application basis. Below is a model of a typical Application policy.

Application Policies define an application as a collection of Secured Entities that represent the discrete functions/components of the application. For example, say we have a three-tier application called PubSite. Our secured entities would be our PubSite Web Servers, our PubSite App Servers, and our PubSite DB Servers. These entities are going to be defined as a category (or the union of multiple categories) or Entity Group which includes the specific VMs involved in that tier/function of the application.

For each Secured Entity, there is an Intra-Tier Rule that defines whether the VMs in the Secured Entity can talk to each other, and if so, how. The Intra-Tier rule has three options: Allow All, Allow Specific2 (and deny everything else), and Deny All. Keep in mind, and this is very important: the intra-tier rule is higher priority than inbounds and outbounds. This means you need to be cautious about creating overly large Secured Entities. You need to keep your Secured Entities small and focused enough that you are comfortable with an allow or deny rule between all of the VMs within the entity. For example, it might be tempting to throw all of your VMs in a single category and use it as the secured entity in an application policy to define universal “any” rules. However, this would require you to define an Intra-Tier rule for that “All VMs” entity which would render any other rules pointless.

VPCs as a policy element is new in FNS 5.2+A policy also includes lists of Inbound Sources and Outbound Destinations. These can be either VMs, Subnets3, VPCs4, Entity Groups, Address Groups, Network Addresses (ad hoc/one-off addresses that don’t necessarily require creation of a reusable Address Group) or Allow All (meaning all IPs).

Finally, the policy is composed of Inbound Rules, which are mappings of an Inbound Source to a Secured Entity with the list of allowed ports and protocols, as well as Outbound Rules, which are mappings of a Secured Entity to an Outbound Destination, with the list of allowed ports and protocols.

It’s important to remember that, due to the nature of microsegmentation and VM-based firewalling, once you secure an application and its constituent VMs with Flow Network Security, only the traffic that you explicitly define via intra-tier, inbound, and outbound rules will be allowed for those VMs. This means you also need to define rules to allow for administrative access (such as SSH or RDP), infrastructure services (such as monitoring, logging, DNS, NTP, or Active Directory), and any outbound internet access required by those servers.

Application Policies are additive. That is, if a VM is in multiple enforced application policies, the effective allow-lists for that VM will include the union of rules from each policy. The Intra-Tier, Inbound, and Outbound rules will be combined into their respective sets with a single implicit deny at the end of the combined list.

Some additional information to keep in mind regarding how these policies are applied:

- A given Application Policy is creating microsegmentation rules for the VMs within the Secured Entities only. The Inbounds and Outbounds are merely referenced in these rules.

- These are stateful rules, meaning that an Inbound rule allows both the incoming traffic and the response.

- Secured Entities within the same policy do not have any inherent trust or rules between them; any traffic between entities must be explicitly defined as inbound and outbound rules. Even though the rules are stateless, each VM is effectively an individual firewall with state being tracked independently. For example, to allow traffic between a web tier and a database tier in the same policy, you need to create an Outbound rule FROM the web tier with the database tier as a destination, as well as an Inbound rule TO the database tier with the web tier as a source.

VDI Policies

VDI policies are a subset of Application policies meant to control traffic to/from VDI desktops based on Active Directory group membership. Active Directory logon events are used to map users to IP addresses. They are only usable on VLAN Subnets. Before VDI policies can be configured, a connection must be established to an Active Directory domain in order to gather identify information and logon events.

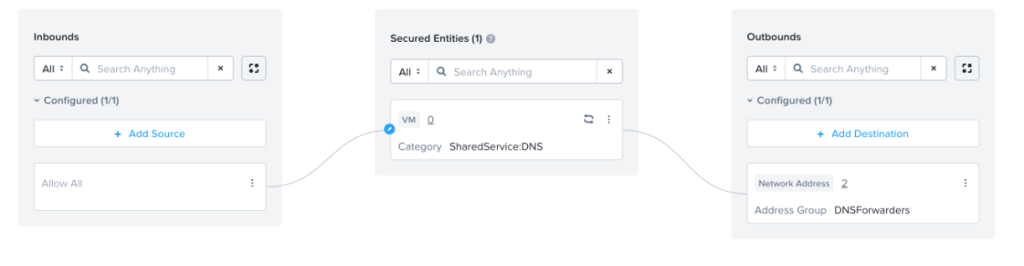

Shared Services Policies

Shared Services policies, introduced in FNS 5.2, are specialized Application policies that are prioritized earlier in the policy chain. They are still comprised of Secured Entities, Inbounds, Outbounds, and rules. However, in a Shared Services policy, the Secured Entities are limited to special SharedService categories that are meant to define infrastructure applications. For example, the default/built-in Shared Services categories are Active Directory, NTP, DHCP, DNS, and SMTP, however the Shared Services Category can be extended with additional values.

A basic example of a Shared Service policy, shown below, defines the organization DNS servers, and allows traffic inbound to the DNS servers, and outbound to any forwarders.

Keep in mind that, while this policy allows the inbound traffic to the DNS servers, you would still need to include the SharedService:DNS category as an outbound for any application policies.

Policy Modes

Shared Service, Isolation, and Application policies have three modes of operation, Saved, Enforced, and Monitor.

Saved

Saved mode allows a policy to be defined but not active. This can be used while a policy is being built or refined without affecting traffic. Saved policies are also useful as templates that new policies can be cloned from.

Enforced

Enforced mode activates the policy completely, allowing only the defined traffic. When a policy results in blocked traffic, that traffic can be displayed as discovered traffic. This can be useful for troubleshooting. If a policy is applied, and an application stops working as expected, you can look at the discovered traffic and identify if a traffic flow was missed. You can easily add it to the policy from there. This also is valuable as a security tool, identifying unexpected traffic flows that require further investigation at the VM level. The example below shows traffic that was blocked, but discovered. Discovered traffic remains visible for 24 hours.

Monitor

Monitor mode is used to observe VMs and identify traffic to or from those VMs. It can be used for gathering information about VMs, or as a way of identifying any unforeseen consequences of a proposed rule before it is enforced. A policy in monitor mode explicitly allows all traffic while identifying what traffic would be blocked according to the policy should the policy be set to enforce mode. Monitor Mode policies are the lowest priority, and only are active for a VM if there are no other enforced policies of any type.

The example below shows a policy in Monitor Mode. No traffic is being blocked by this policy, but we are able to see what WOULD be blocked if this policy were enforced.

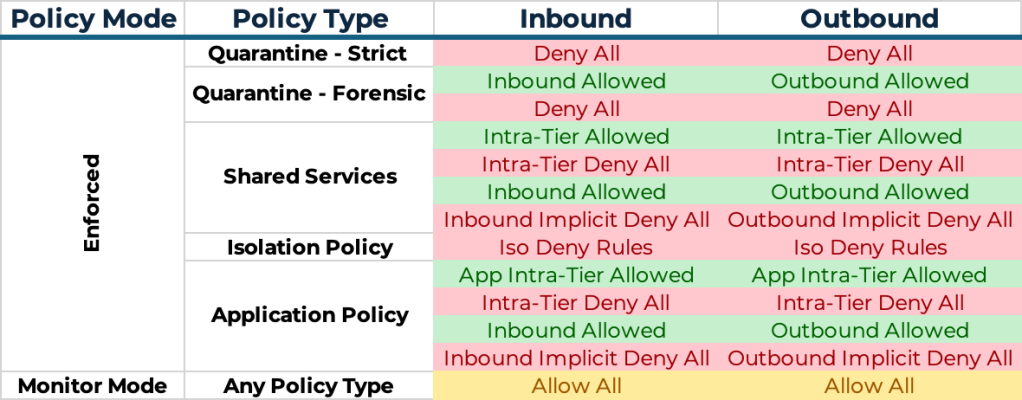

Policy Priority

The chart below breaks down the different policy and rule types and their prioritization. Note that the chart below is effective as of FNS 5.1. In prior versions, Monitor policies are prioritized above Isolation & Application policies. Also note that Shared Services policies are new as of FNS 5.2.

Quarantine is the highest priority. Any VM found to be a member of the Quarantine:Strict category and therefore subject to a Quarantine Strict policy will have all inbound and outbound traffic denied. Next, the Quarantine Forensic policy is applied to any VMs in the associated category, which allows only traffic outbound to destinations defined in the policy, with any other traffic denied.

If a VM is not quarantined, any enforced Shared Services policies would be effective, with the Intra-Tier rules being evaluated before inbounds and outbounds. Any traffic not allowed by an enforced Shared Services policy would be denied. No further policy evaluation is required.

The next priority would be any enforced Isolation policies. These policies are unique in that they act as specific explicit deny rules to prevent specific entities from communicating. As they only deny the specific traffic between isolated entities, all other traffic would be allowed unless the VM is also subject to an Application policy.

Enforced application policies are next. As discussed above, if a VM is in one or more application policies, it ends up with effective intra-tier, inbound and outbound “allow lists” that are the sum of all “allowed” traffic from all applicable policies. These combined effective “allow lists” are followed by implicit deny all rules.

If no enforced policies apply, monitor policies are considered next. As stated, Monitor policies do not block any traffic; they provide data on what the result would be if the policy were enforced.

During evaluation, once a packet hits either an Allow or Deny action, no further processing takes place. Finally, we see that a VM that isn’t subject to any policies will not be policed by Flow Network Security at all, and all traffic will be allowed.

Some Guidelines for Creating Policies

Note: I am a Senior Staff Consultant with the Nutanix Professional Services team. The following section is taken from my Getting Started with Flow Network Security 5.2 guide, which I wrote to help clients get started with FNS.

There are different choices you might make when building policies, and so I’m going to walk you through some of the questions I ask clients to ensure they are making the choices that are best for them.

Handling Internet Traffic

Presently, Flow Network Security does not allow DNS-based destinations, and the proliferation of CDNs and globally distributed applications makes it difficult to define internet destinations solely by IP address. Additionally, in most cases, we’re doing deeper inspection of internet traffic at a perimeter firewall, with features such as category filtering, SSL inspection, and data-loss prevention.

In this case, one potential solution is to create a Network Address group for Public Subnets, defining the known public IP space. To define this Public Subnets group, you can use the following 9 IP ranges:

- 1.0.0.0 – 9.255.255.255

- 11.0.0.0 – 126.255.255.255

- 129.0.0.0 – 169.253.255.255

- 169.255.0.0 – 172.15.255.255

- 172.32.0.0 – 191.0.1.255

- 192.0.3.0 – 192.88.98.255

- 192.88.100.0 – 192.167.255.255

- 192.169.0.0 – 198.17.255.255

- 198.20.0.0 – 223.255.255.255

You can then allow outbound access via HTTP, HTTPS, and any other chosen protocols. This traffic to Internet IPs will eventually end up at our perimeter firewall, where it can be appropriately inspected and allowed or denied.

Other options do exist, such as:

- using web proxy servers as a single point of internet egress

- using Service Insertion to redirect internet traffic through VM-based firewalls

Inbound/Outbound vs. Inbound Only

One of the first questions I ask a client when I’m meeting with them is always “What is your goal in implementing microsegmentation?” The answer generally lands in one of two camps and will strongly inform the approach we take when designing policies.

The first is “I want to protect my vital servers and data.” These organizations understand that they have high-value applications with important data, and their goal is to protect those specific applications and their data. They aren’t necessarily looking to fully implement microsegmentation, but they understand that, for instance, a ransomware incident spreading to those vital servers would be catastrophic. These organizations might focus only on policing inbound traffic to their protected applications and leaving outbound traffic from our application open.

The second is “I am looking to implement a Zero-Trust security posture.” These are organizations looking to fully lock down their environment, allowing only explicitly defined traffic and blocking everything else. These organizations are going to want every VM in their environment to be subject to a security policy, and those security policies to explicitly define inbound AND outbound traffic.

Let me be clear: both approaches are 100% valid! There’s an old saying: Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. I’ve heard many organizations say, “We don’t have the manpower to implement a full Zero-Trust security posture, so we can’t use microsegmentation,” and it makes me want to tear my hair out. Yes, every organization’s long-term goal SHOULD be Zero-Trust! However, you have to start somewhere, and building policies to prevent unwanted traffic to your vital servers in data is a perfect, and more importantly, manageable way to start!

Single-Site or Multi-Site: Categories or Address Groups?

When you design policy, you need to consider where our sources and destinations are, and where they might end up. When referencing VMs by category or entity groups, we are limited to the VMs that are managed by our Prism Central. Therefore, we need to consider disaster recovery scenarios and how those might affect our policies.

Consider a policy that, because of the categories selected, allows inbound traffic from VM-1 to our secured entity VM-2. If VM-1 were to be failed over to another availability zone (and therefore another Prism Central’s management), this policy would, in a manner of speaking, lose sight of VM-1, as our local Prism Central would no longer have VM-1 in inventory or be aware of the IP addresses assigned to VM-1. In this scenario, where it is possible that a DR event might separate VM-1 and VM-2, it would be better to reference VM-1 by way of Network Address Groups that could account for VM-1’s potential differing IP addresses during standard operation as well as DR failover. If, however, VM-1 and VM-2 will ALWAYS failover together and will ALWAYS be managed by the same Prism Central, you can continue to use categories and/or entity groups for your inbounds and outbounds.

Template Policies: What Applies to Everything?

Often there are infrastructure services and rules that apply to every VM or many VMs. In these cases,I suggest building template policies that already have those inbounds, outbounds, and rules defined. Every policy would then start as a clone of the template, saving time. I recommend creating a PolicyTemplate:Placeholder1/2/3/4 categories and building a template policy with those placeholders as secured entities. From there, you can clone your policy, replace the placeholder entities with the real entities, and if you have fewer than 4, delete the extra. An example of what this might look like is shown here:

Policy Placement Considerations

One of the guiding rules for policing traffic is to place policies as close to the source as possible. When planning security policies, I recommend having a diagram of your network on hand, allowing you to visually trace the traffic and identify the enforcement point nearest to the source.

Consider an environment with a perimeter firewall, a transit VPC, and a tenant VPC. Inbound traffic from the internet should be policed at the perimeter firewall, minimizing unnecessary traffic from hitting the transit VPC’s virtual router at all. Outbound traffic, however, should be policed as close to the source as possible. So, if your licensing allows for microsegmentation policies via Flow Network Security, you should police outbound traffic there, allowing the policy to be enforced as close to the source as is possible.

East/West traffic between VMs in a VPC should also ideally be handled by microsegmentation policies. in addition, network policies at the VPC virtual router can act as a backstop at the subnet level. Remember that security policies are processed at the VM level, whereas network policies are only processed when traffic is routed by the VPC virtual router.

Finally, take advantage of monitor policies and traffic discovery. Microsegmentation policies are an exceptionally powerful tool for protecting an organization against ransomware or other malware attacks as they can very effectively limit the horizontal blast radius should an individual VM be compromised. However, to be completely effective, they must be very thorough. This requires that you truly understand the traffic flow in your environment. Make liberal use of monitor policies, and ensure that you can identify all discovered traffic. Use this discovery information to write your policies as close to a zero-trust mindset as possible. That is, consider any traffic that you cannot explicitly identify and allow as valid as untrusted, and therefore blocked. In addition, ensure that you routinely are auditing policies and category membership to ensure that the effective policy matches the expected policy.